Perceptual Details

Such information differences make!

An anomaly is a difference. A deviation. Some noticeable variation.

Ponder this for a moment: there is no information in sameness.

Where a fog obscures vision beneath and behind a gray cover of “all-alikeness”, nothing can be seen. All the differences that might inform one’s senses are unavailable. There is only fogginess.

An anomaly is a difference. A deviation. Some noticeable variation.

Ponder this for a moment: there is no information in sameness.

Where a fog obscures vision beneath and behind a gray cover of “all-alikeness”, nothing can be seen. All the differences that might inform one’s senses are unavailable. There is only fogginess.

Undifferentiated space presents a sameness of vacancy — emptiness, no perceptible differences.

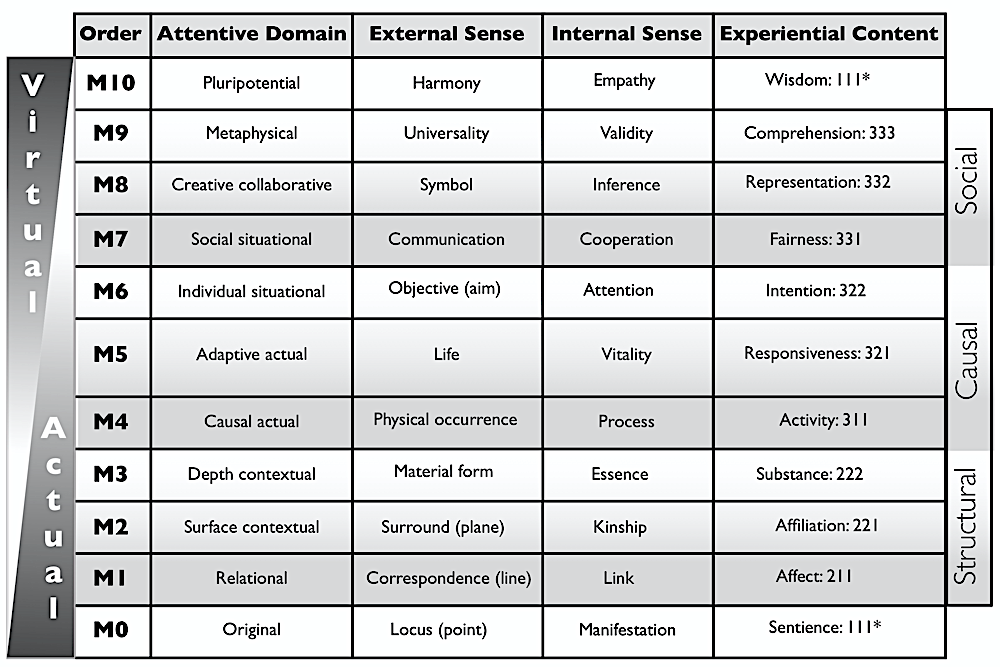

Something manifests only where perceived differences occur. And depending upon the complexity of that something, it too comprises many contrasts. Coloration. Texture. Heft, or weight. We perceive those various types of information in different orders of complexity. The attentive orders, M0…M10, catalog degrees of elaboration that characterize these different levels of information organization, from the simplest to the most complicated. (See the table Manifest Orders of Attentive Domains, below.)

Contrasts within more complex orders are nested, the simpler being a feature of some greater organization of details. Some are scattered across an expanse. The complexity of that expanse evokes notions of 1D, 2D, 3D, etc., spatial dimensions. Some features may be hidden on a far side, but are anticipated or remembered from prior experience.

The substance, the “stuff” of a “something”, is inferred from a totality of its properties and characteristics, which are perceived in terms of sensed differences, both within the entity itself and in contrast to other things.

A familiar item is recognized by comparing it with remembered schemas of how the features of similar items are organized. A totally novel thing may invite our curiosity into exploration, even to probe its actuality by sketching its features. We peruse it to familiarize ourself with its unique form. Its unfamiliar differences are assimilated into our repertoires of the familiar.

A formal definition of information depends upon a notion of the bit, the smallest discernible difference in something. The more complicated that something is, the more bits are needed to characterize it.

Basic attentiveness exercises the linear order of M1, the simplest organization of information that relates a pair of locations, or through a sequence of such directed relationships. There, direct action affects things and relations between them.

Something manifests only where perceived differences occur. And depending upon the complexity of that something, it too comprises many contrasts. Coloration. Texture. Heft, or weight. We perceive those various types of information in different orders of complexity. The attentive orders, M0…M10, catalog degrees of elaboration that characterize these different levels of information organization, from the simplest to the most complicated. (See the table Manifest Orders of Attentive Domains, below.)

Contrasts within more complex orders are nested, the simpler being a feature of some greater organization of details. Some are scattered across an expanse. The complexity of that expanse evokes notions of 1D, 2D, 3D, etc., spatial dimensions. Some features may be hidden on a far side, but are anticipated or remembered from prior experience.

The substance, the “stuff” of a “something”, is inferred from a totality of its properties and characteristics, which are perceived in terms of sensed differences, both within the entity itself and in contrast to other things.

A familiar item is recognized by comparing it with remembered schemas of how the features of similar items are organized. A totally novel thing may invite our curiosity into exploration, even to probe its actuality by sketching its features. We peruse it to familiarize ourself with its unique form. Its unfamiliar differences are assimilated into our repertoires of the familiar.

A formal definition of information depends upon a notion of the bit, the smallest discernible difference in something. The more complicated that something is, the more bits are needed to characterize it.

Basic attentiveness exercises the linear order of M1, the simplest organization of information that relates a pair of locations, or through a sequence of such directed relationships. There, direct action affects things and relations between them.

Ancient modes of attentiveness taken for granted

Early attentive modes at M1 typically go unnoticed after childhood. Sequences of simple acts that have been made into habitual patterns of behavior generally occur so casually as almost to be unconscious, except where something doesn’t go quite as expected. Then, an inconvenienced adult may pause to methodically ascertain the source of some hitch in plans, the cause of some hangup.

The kinship of difference and information has occupied humans for eons. It is registered in the very first signs of human attentiveness at sites of ancient habitation. By interpreting differences among differences, as well as similarities among similarities, left by our earliest forebears, we gradually decipher what likely were their circumstances and capabilities. We attentively exploit and explore those abilities still.

Early attentive modes at M1 typically go unnoticed after childhood. Sequences of simple acts that have been made into habitual patterns of behavior generally occur so casually as almost to be unconscious, except where something doesn’t go quite as expected. Then, an inconvenienced adult may pause to methodically ascertain the source of some hitch in plans, the cause of some hangup.

The kinship of difference and information has occupied humans for eons. It is registered in the very first signs of human attentiveness at sites of ancient habitation. By interpreting differences among differences, as well as similarities among similarities, left by our earliest forebears, we gradually decipher what likely were their circumstances and capabilities. We attentively exploit and explore those abilities still.

Left: Hand silhouettes, more than 10,000 years old, from caves of Borneo

Right: “Petroglyph of labyrinth” from Meis, Galicia, c. 2000 BC, photo by Froaringus, CC-BY-SA 3.0

Right: “Petroglyph of labyrinth” from Meis, Galicia, c. 2000 BC, photo by Froaringus, CC-BY-SA 3.0

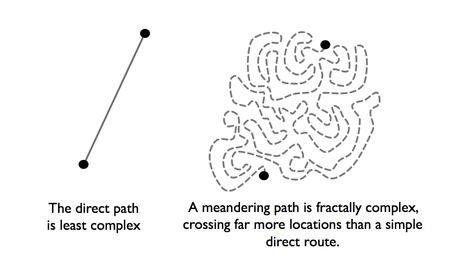

Information construed at M1

A perfectly straight line expresses information about the most direct route from one point to another, but little else. There is only one direct route between two given locations. But there is no limit to the number of different meanders that may connect any two points.

Both occur at M1, but the meander is more complex than a direct route”. Also, the straight path between two points is determined by just the two locations. But a meander must be thought of as a sequence through a multitude of different locations. A meander can be construed as a more complicated sequence of tiny straight segments! It is not yet fully 2-dimensional, but approaches planarity, at order M2. Thus, fractal dimension is given as a fraction. At M1 a meander might qualify for a fractal dimension of 1.47, or 1. 83, while a straight line expresses only 1.0. (The mathematics of such calculations are beyond the scope of present concerns.)

A perfectly straight line expresses information about the most direct route from one point to another, but little else. There is only one direct route between two given locations. But there is no limit to the number of different meanders that may connect any two points.

Both occur at M1, but the meander is more complex than a direct route”. Also, the straight path between two points is determined by just the two locations. But a meander must be thought of as a sequence through a multitude of different locations. A meander can be construed as a more complicated sequence of tiny straight segments! It is not yet fully 2-dimensional, but approaches planarity, at order M2. Thus, fractal dimension is given as a fraction. At M1 a meander might qualify for a fractal dimension of 1.47, or 1. 83, while a straight line expresses only 1.0. (The mathematics of such calculations are beyond the scope of present concerns.)

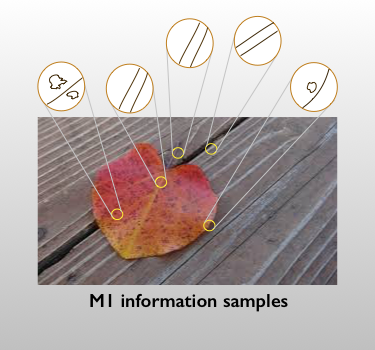

Turning over an old leaf

This morning I picked up from my porch the derelict, insect- and weather-ravaged remains of an oak leaf (it’s now mid-November here). Ordinarily I’d likely pass it by, unnoticed. But, given attention, the uniqueness of the leaf scrap readily becomes apparent. It's outer contour varies, but sufficient clues remain to suggest its common name, red oak. Some portions are similar, though none are precisely straight. Other segments meander through irregularities wreaked by insects or weather damage. There’s not another leaf quite like this one anywhere that I could ever hope to find. The silhouette of its remnant shape and appearance express a litany of unique experiences within its life-cycle. It is individual in its visible particulars.

This morning I picked up from my porch the derelict, insect- and weather-ravaged remains of an oak leaf (it’s now mid-November here). Ordinarily I’d likely pass it by, unnoticed. But, given attention, the uniqueness of the leaf scrap readily becomes apparent. It's outer contour varies, but sufficient clues remain to suggest its common name, red oak. Some portions are similar, though none are precisely straight. Other segments meander through irregularities wreaked by insects or weather damage. There’s not another leaf quite like this one anywhere that I could ever hope to find. The silhouette of its remnant shape and appearance express a litany of unique experiences within its life-cycle. It is individual in its visible particulars.

Leaf remnant, its outer M1 contour and contour inflections

There is a lot of information given, even in just the outer contour of this remnant where, at attentive order M1, changes of direction, from location to nearby location, describe distinguishing contours of a path traced along its edge.

I’ve marked major inflections in that contour — where the direction, to the naked eye, appreciably shifts. Complex though it may seem, all anomalies of contour still have not been marked. Zooming in on the actual leaf would reveal an entirely overlooked order of zigs and zags at smaller scale than the ones indicated here.

I’ve marked major inflections in that contour — where the direction, to the naked eye, appreciably shifts. Complex though it may seem, all anomalies of contour still have not been marked. Zooming in on the actual leaf would reveal an entirely overlooked order of zigs and zags at smaller scale than the ones indicated here.

Manifest Orders of Attentive Domains

'

Perceptual process largely is pre-conscious

As Tor Norretranders points out in The User Illusion, most of the information presented to the conscious mind is interpreted at an unconscious, intuitive level. From those layers of pre-processing one formulates strategic and tactical scenarios of anticipation and logical decision making. It is important to recognize that analogical intuition unconsciously constructs a perceptual scenario within which the conscious use of linguistic skills in logical reasoning take place. Only amid a-logically construed (analogical) situations can the focused logic of linguistic reasoning navigate likely outcomes of occurrence and happenstance. To fully understand a circumstance, one must first comprehend how it is perceived and how that perception anticipates one's mental biases.

In Wholeness and the Implicate Order, physicist David Bohm decries the fragmentary, convergent logic of modernist thinking. He finds it too narrowly focused in object-orientation of the reductionist materialist legacy of our C4 cultural scientism.

The modern mind blinds itself to deeply crucial organic flows of events and circumstances that once were celebrated in ancient doctrine and now have been reborn from implications of both quantum and relativity physics. Bohm suggests that western languages, with their subject-verb-object structures are a major factor in our tendency to misconstrue complexly interacting processes as mere substantial objects. Our linguistic habits obscure an essentially dynamic interrelatedness of all phenomena and entities. He even suggests forming a new verb-specific mode of western languages, the rheomode, coined from the Greek word “rheo” for “flowing”, to help overcome the misleading object biases of modern languages.

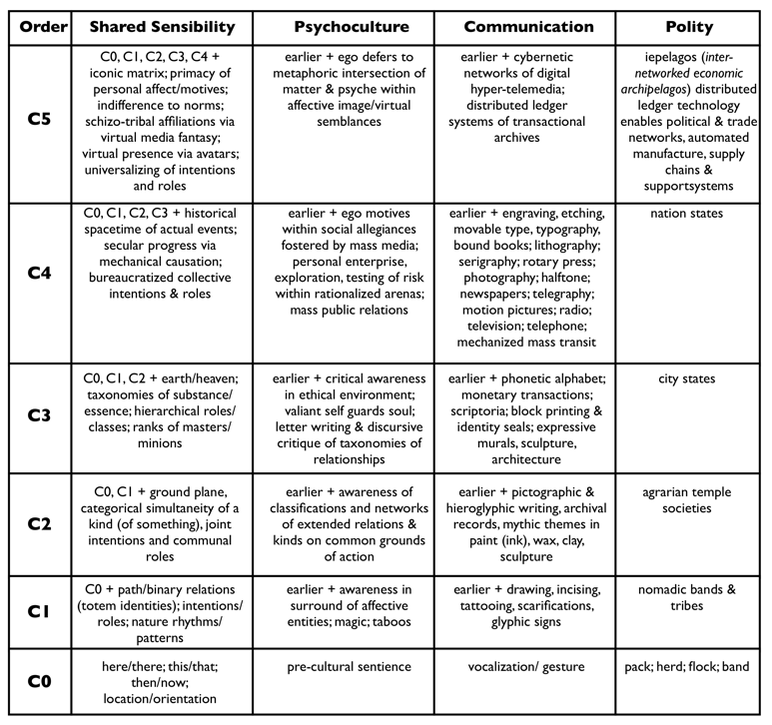

One of Bohm’s colleagues, physicist F. David Peat, agrees and has written a book, Blackfoot Physics, that attempts to convey a cultural counter-view to the C4 modern, from the C1 and C2 vantages of aboriginal traditions, such as those continuing among North American native tribes that speak the Algonquin group of languages. (See the table, Evolution of Cultural Orders, below.) In writing of Blackfoot culture, Peat says,

Within the chapters of this book can be found discussions of metaphysics and philosophy; the nature of space and time; the connection between language, thought, and perceptions; mathematics and its relationship to time; the ultimate nature of reality; causality and interconnection; astronomy and the movements of time; healing; the inner nature of animals, rocks, and plants; powers of animation; the importance of maintaining a balanced exchange of energy; of agriculture; of genetics; of considerations of ecology; of the connection of the human being to the cosmos; and of the nature of processes of knowing. In addition, there are references to technologies such as the Clovis spear point, ocean-going vessels and birchbark canoes, tepees and longhouses, the development of corn and other plants, farming methods, observation astronomy and record keeping, and the preparation of medicines from various sources. [Location 42 of the ebook version.]

Perceptual process largely is pre-conscious

As Tor Norretranders points out in The User Illusion, most of the information presented to the conscious mind is interpreted at an unconscious, intuitive level. From those layers of pre-processing one formulates strategic and tactical scenarios of anticipation and logical decision making. It is important to recognize that analogical intuition unconsciously constructs a perceptual scenario within which the conscious use of linguistic skills in logical reasoning take place. Only amid a-logically construed (analogical) situations can the focused logic of linguistic reasoning navigate likely outcomes of occurrence and happenstance. To fully understand a circumstance, one must first comprehend how it is perceived and how that perception anticipates one's mental biases.

In Wholeness and the Implicate Order, physicist David Bohm decries the fragmentary, convergent logic of modernist thinking. He finds it too narrowly focused in object-orientation of the reductionist materialist legacy of our C4 cultural scientism.

The modern mind blinds itself to deeply crucial organic flows of events and circumstances that once were celebrated in ancient doctrine and now have been reborn from implications of both quantum and relativity physics. Bohm suggests that western languages, with their subject-verb-object structures are a major factor in our tendency to misconstrue complexly interacting processes as mere substantial objects. Our linguistic habits obscure an essentially dynamic interrelatedness of all phenomena and entities. He even suggests forming a new verb-specific mode of western languages, the rheomode, coined from the Greek word “rheo” for “flowing”, to help overcome the misleading object biases of modern languages.

One of Bohm’s colleagues, physicist F. David Peat, agrees and has written a book, Blackfoot Physics, that attempts to convey a cultural counter-view to the C4 modern, from the C1 and C2 vantages of aboriginal traditions, such as those continuing among North American native tribes that speak the Algonquin group of languages. (See the table, Evolution of Cultural Orders, below.) In writing of Blackfoot culture, Peat says,

Within the chapters of this book can be found discussions of metaphysics and philosophy; the nature of space and time; the connection between language, thought, and perceptions; mathematics and its relationship to time; the ultimate nature of reality; causality and interconnection; astronomy and the movements of time; healing; the inner nature of animals, rocks, and plants; powers of animation; the importance of maintaining a balanced exchange of energy; of agriculture; of genetics; of considerations of ecology; of the connection of the human being to the cosmos; and of the nature of processes of knowing. In addition, there are references to technologies such as the Clovis spear point, ocean-going vessels and birchbark canoes, tepees and longhouses, the development of corn and other plants, farming methods, observation astronomy and record keeping, and the preparation of medicines from various sources. [Location 42 of the ebook version.]

Cultural Orders

Attending the flow of experience

Rather than augmenting deficiencies in one’s native language or learning to speak an older, more organically structured one, perhaps one merely needs to pay attention to acts of paying attention.

For generations of our ancestors, a complete education for every enlightened and informed individual included study and development of perceptual skills through drawing, painting and sculpting, as well as instruction in the arts of music and dance. It is in those aesthetic — i.e., perceptually fluent — disciplines that the dynamic character of organic form is most directly studied and appreciated.

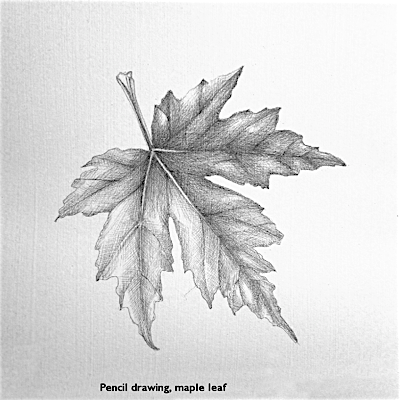

The organic unity of the process of seeing and comprehending is revealed in such an image as the pencil drawing of a maple leaf, shown below. A dynamic of perception and physical rendering are shown in the clarity and coherence of information about each part of the form given in relation to everything else — including empty or overlapped surrounding planar areas. Details of rendered forms are perceived and executed at attentive order M1; they are organized at M2 in a pattern, also called a gestalt.

Such coherence is a source of the vitality “felt” enlivening any truly organic structure. It arises from analogical relationships — matters of difference and similarity — found among all parts of a whole, rendered so as to convey a rhythmically coherent sense of the total M2 gestalt, the over-all perceptual pattern of organized sensory information.

Rendering attended form

The pencil drawing of a maple leaf reveals rhythmically distributed configurations of information. Visual differences are captured in terms, not only of shape contour, but also in lights and darks of shaded surfaces, skeletal lines of leaf veins, etc.

An important part of the pencil drawing’s appeal is a holistic interaction between shapes of the leaf lobes and “negative spaces” they carve as empty voids between. The shape of the voids is as informative as the positive contours of the leaf itself. And they relate its form to the framing space of the image format, itself, to convey a visually arresting image.

Perceptual relationships construed among similarities and differences of characteristics are built analogically.

Schematic ideas of actual forms are construed organically. Their individual features are gathered simultaneously. They emerge within an intuited structure wherein affinities and contrasts are inferred as characteristics and properties of a greater perceived whole. All-at-once details become the construed pattern of perceptual gestalt that unites many levels of attentiveness into organically coherent awareness.

Linear sequences of logical reasoning depend upon those readied realizations of perceived form and circumstance. Form differences and the relations among them already have been analogically construed by perceptual process into coherent wholes before logical reasoning deduces causal particulars from properties described by the information they bear.

Ordinarily, one’s mind processes such information automatically, with little notice. But learning to draw attentively engages many such particulars. One learns not only to pay attention to the slightest waver of an edge, in relation to other wavers and pulses nearby, but also to matters of shading and coloration, of texture and placement. Gradually, with much repetition, the hand learns to translate visually perceived form into configurations of elegant, or forceful, or subtle, or whatever style of stroke seems appropriate. Repeatedly, in such work, M1 linear evocations of value and color are strategically configured and deployed across a planar expanse, in an over-all pattern construed at attentive order M2, across the surface of some receptive medium.

Now, keep in mind that all of the information gathered into an inflected line is but a construction of mind. It is virtual and abstract. As frequently pointed out by Ingres, Durer and countless other artists through the centuries, “Line does not actually exist in nature.” It is only construed as a virtual product of perceived form, an abstraction.

Learning to draw well

At its simplest, drawing is merely a matter of observing and interpreting such placement of linear deviations as visual information.

For those desiring to explore what drawing can teach the burgeoning mind, Betty Edwards’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, presents an introductory course of exercises suitable for either classroom or self-study. Anyone capable of buttoning a shirt or tying a tie in the mirror has the ability to draw well. And dismissal of such a notion by declaring one’s lack of “talent” or an inability to “draw a straight line” is answered by observing that everyone, especially artists, use rulers or other straightedges to draw such lines when needed. And no special talent is needed to draw well. Ordinary physical and mental competence more than suffices. Drawing well is not about straightness, nor talent, nor even about realistic likeness, which takes care of itself with experience and enhanced proficiency honed by practice.

And beyond drawing, for more extensive visual studies, try Calvin Harlan's wonderful little study guide, Vision and Invention: An Introduction to Art Fundamentals. There you'll encounter the foundational notion that seeing well and clearly is a matter of appreciating the complementing contrasts that accompany any perception of difference.

Drawing well ultimately is about appreciating and economically rendering perceptual information, mostly at M1 and M2, to convey dynamic and organic sense of M3 forms. Learning to draw exercises the most crucial of awarenesses, the organic dynamics of cognitive wholeness, M0 context both of self and of world.

Through drawing one exercises and explores what is perceived and how it is perceived. Such active insight gets at the root of what one knows and how it is known, and is fundamental to sensibilities of all higher Manifest Orders.

Now, keep in mind that all of the information gathered into an inflected line is but a construction of mind. It is virtual and abstract. As frequently pointed out by Ingres, Durer and countless other artists through the centuries, “Line does not actually exist in nature.” It is only construed as a virtual product of perceived form, an abstraction.

Learning to draw well

At its simplest, drawing is merely a matter of observing and interpreting such placement of linear deviations as visual information.

For those desiring to explore what drawing can teach the burgeoning mind, Betty Edwards’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, presents an introductory course of exercises suitable for either classroom or self-study. Anyone capable of buttoning a shirt or tying a tie in the mirror has the ability to draw well. And dismissal of such a notion by declaring one’s lack of “talent” or an inability to “draw a straight line” is answered by observing that everyone, especially artists, use rulers or other straightedges to draw such lines when needed. And no special talent is needed to draw well. Ordinary physical and mental competence more than suffices. Drawing well is not about straightness, nor talent, nor even about realistic likeness, which takes care of itself with experience and enhanced proficiency honed by practice.

And beyond drawing, for more extensive visual studies, try Calvin Harlan's wonderful little study guide, Vision and Invention: An Introduction to Art Fundamentals. There you'll encounter the foundational notion that seeing well and clearly is a matter of appreciating the complementing contrasts that accompany any perception of difference.

Drawing well ultimately is about appreciating and economically rendering perceptual information, mostly at M1 and M2, to convey dynamic and organic sense of M3 forms. Learning to draw exercises the most crucial of awarenesses, the organic dynamics of cognitive wholeness, M0 context both of self and of world.

Through drawing one exercises and explores what is perceived and how it is perceived. Such active insight gets at the root of what one knows and how it is known, and is fundamental to sensibilities of all higher Manifest Orders.